THE LIMA CULTURE AND WATER []

First published January 21, 2011 by Andean Air Mail & PERUVIAN TIMES

The seventh in a series on Peru’s history, incorporating stories from the Peruvian Times archives, as well as links to videos, audios and other external sources to provide a rich background of information. Part 1 The Dawn of Urbanization ; Part 2 Tour 3000 BC to 500 AD ; Part 3 Monumental Architecture ; Part 4 Transition; Part 5 The Pucllana Period; and Part 6 Reading the Past, Righting the Record.

If writing had been a “scarce commodity” in the Pucllana period, water was another: water has always been western Peru’s number-one scarce –but perversely sometimes too abundant– resource. There had been varying years of a desert climate interspersed with rare mud slides and flash floods (huaycos). But by about 200 AD the Lima culture was about to flower, watered by a growing network of irrigation canals – one of the hidden wonders of the Rimac estuary (they are now underground, having been incorporated into the city’s sewage system).

Where were these canals? Can we see them today? When visiting an early archaeological site ask the guide: where was the canal, river or water supply? Continuing our examination of the four W’s: writing, water, wheels and wagons…

The watercourses Huatica and Surco

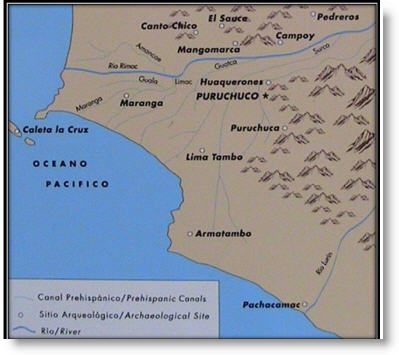

Within living memory, the watercourses called Huatica and Surco bubbled their way through the countryside of what is now metropolitan Lima. Unlike real rivers or tributaries they did not flow into the main river, the Rio Rimac, but rather distributed water from the Rimac to quite distant parts of the valley and estuary. The Surco (or Sulco), for example, was constructed from a point well to the east of the later colonial city (see map below) right through to the feet of the ancient pilgrimage “tambo-town” of Armatambo not far from the Pacific Ocean and in the present-day district of Chorrillos. Huatica and Surco were, in fact, prehispanic irrigation canals. Only the passage of time had conferred irregular features on them and occasionally native trees such as the guarango would root themselves in the banks to lend these canals the aura of authentic rivers.

A basic infrastructure grid for the “garden city”

A basic infrastructural grid for the “garden city” of Lima had been laid down by 200 BC, if not before. That is an approximate date for a transition from buildings that were truly monumental in scale, with massive (10 hectares or more) central plazas watered by canals or rivers to “more modest” structures such as the Huallamarca truncated pyramid in San Isidro [See Part 5]. By 200 AD the “Lima Culture” was flourishing with hundreds of structures in what is now the metropolitan Lima area, scattered alongside an extended network of canals.

Many of these irrigation courses still exist and supply water to some of the most beautiful parks in Lima, though in the main the canals are invisible to the casual viewer as they now lie underground. (But also, it must be said,serve as sewers!) The most ambitious of the canals is the Surco, which supplied water to the many chacras or fields lying between the River Rimac and Armatambo on the ancient road between Maranga (City of World Culture 400 AD) and Pachacamac (Top Pacific Coast Oracle 800 AD).

Armatambo is or was to be found at the foot of the Morro Solar that rises up behind Chorrillos. (A resident of Chorrillos told me recently that Armatambo to her was “un pueblo joven – y nada más” ). It is also not far from the exclusive Regatas club. However, the Armatambo Cruz Pyramid (together with La Lechuza -see Wikimapia below) is important to early historians as it is one of the last remains of the Armatambo settlement, which served as the capital of the “gran curacazgo o señorío” (the great chiefdom or estate) of Sulco before the Inca domination of the Lima valley. Today one of the principal intellectual guardians of Armatambo is Rogger Ravines. His drawing of the urban plan is shown below.

The main canals are marked on the map with the following “labels”: Huaquerones (which irrigates the fields in front of the restored mansion of the Puruchuco curacazgo in Ate-Vitarte), Surco, Guat(i)ca, Limac, Guala, Maranga (not necessarily their original names). Note that these (thin blue) watercourses on the map are not tributaries but (were) irrigation canals, i.e. the flow is not into the Rimac. [Photo of map above from the Museo de Sitio, Puruchuco. Photo: P Goulder].

The mill on the Huatica

Wander through the Barrios Altos (downtown, south-east of Avenida Abancay) of Lima in the 1920’s and shortly after passing the church of Santa Clara you will encounter the mill that once lay alongside the “Rio” Huatica (the Convento y Edificio del Molino de Santa Clara), but the statues have long gone). As you wander, wonder if the mill was driven by the waters of the Huatica, by the winds bearing up the valley or indeed whether - before the Spanish – how water was harnessed without the wheel. The church itself is little changed over time except for the graffiti and deprivation around.

As a detour from our “water history,” you can visit also one of the great surviving “quintas” from the short-lived golden era of the first half of 20th century Lima: the Quinta Heeren nearby – see map. A= Santa Clara. The quinta is to the rear.

Travel further out to the groves of El Olivar in San Isidro, to the old olive press, and take a seat near the Municipalidad. Sooner or later during the day hatches in the grass are removed and turbid water oozes to the surface. In the torrid days of February the water gushes. When I last had time to sit and observe, the water was apparently mixed with sewage from further upstream.

Peggy Massey was another Olivar watcher and a correspondent from El Comercio observed in 2007 that “The parks have become polluted because there are no proper standards for irrigation water. Most districts (boroughs) use contaminated irrigation canals. Surco, San Miguel and Miraflores treat the effluent. San Borja will be doing so in August. . (The standards have since been upgraded). Nevertheless, it is wonderful that we can still see evidence of the old canals.

PIC5

Surco to Ichimatampu (Armatampu / Tambo)

The Surco canal and hacienda share their name with the district of Surco (a field furrow, Spanish, but the provenance of the name could be the reverse) and supplies water to, for example, the complex of parks and nurseries that lie between Higuereta and Avenida Ayacucho in (of course) Surco. Surquillo was the name of a large hacienda near Limatambo. We will return to the search for the hidden water infrastructure of Lima in later parts of the series. But was Lima really a garden city set amongst gleaming canals – a hybrid of Venice and the tulip fields of Holland somehow overlooked by the early chroniclers? What seems to be true is that Astete (Estete) in the 16th century recorded much else but failed to note the canals and constructions of the Rimac valley, even though he was the encomendero, in charge of the upper valley. Many since have believed incorrectly that the Rimac valley was a barren desert when Pizarro arrived. PIC6

Right: Inner rectangle – the Armatambo Cruz Pyramid, “One of three remaining huacas, flat-topped pyramid-like structures at the urban complex of Ichimatampu (Armatambo), which was strategically located at the head of the Surco canal, midway between Maranga and Pachacamac and at the foot of the Morro Solar.” The road, top centre to bottom right, is Julio Calero. Retrieved from Wikimapia.

Five independent drainage basins

At the risk of being repetitive and spurred on by friends who refuse to believe that the Lima area contained a flourishing urbanized, “watered” civilization prior to Pizarro, Part 7 signs off with a brief quote, written in 1989, from anthropologist José Matos Mar: “The present system of collection and disposal of wastewater from Lima has its antecedents in the pre-Hispanic indigenous irrigation canals that irrigated the vast delta of the Rimac valley. Indigenous irrigation canals had a decisive influence on the technical characteristics and the design of the current system for the disposal of wastewater. . . which utilizes the five, mainly independent, drainage areas that still discharge at different points along the coast.”

Incidentally

Ironically, the Leeds and Liverpool Canal in the UK became in the early 19th century an important artery for the export of wool and camelid fibers from the Altiplano to the twin mills in Bradford, which received them via Liverpool. The Titus Salt (yes, that was his name) Mill just to the North of Bradford has become iconic – complete with llamas on the roof – and (but!) has become an art gallery. In turn the wool towns of Arequipa and Sicuani experienced golden periods first as llama/mule and then steam train centers, handling the wool and fiber trade.

Anglophone Peruvianists have taken a more than casual interest in canals. For example Anne Kendall has dedicated a good part of her professional life to “bringing the Inca canals back to life” (See Sally Bowen, 1996)” and in the process established a formidable reputation in the field.

And the extensive research into Inca engineering achievements in the use and management of water has been a long-standing project of Kenneth and Ruth Wright of Colorado, who have been honored with Peru’s Order of Merit and also recently recognized for their work by Peru’s Engineering University.

In 2008, archaeologists confirmed advanced hydraulic system in Andean fortress – “Archaeologists from the National Institute of Culture have reportedly uncovered three irrigation channels that confirm the existence of an advanced hydraulic system in the Sacsayhuaman fortress located on the periphery of the former Inca capital of Cusco. According to Agencia Andina, the irrigation system was designed by Inca Pachacutec.”

NEXT PART – Part 8: Before embarking on our second tour, which will encompass the advent of three empires: Huari, Inca and Spanish in the period from about 700 to 1600, we need to deal with the other great technological and artistic developments of the Lima Culture period: embroidery, weaving and metallurgy.

Links to the previous articles in this series found in the Journal of Peruvian Studies: Part 1 The Dawn of Urbanization; Part 2 Tour 3000 BC to 500 AD ; Part 3 Monumental Architecture ; Part 4 Transition; Part 5 The Pucllana Period; and Part 6 Reading the Past, Righting the Record.